On Sunday afternoon, October 19, I spent a few hours volunteering at a “phone bank” for the Obama campaign. Not because I support Obama, mind you, but simply to get an idea of what goes on at these events and to see first-hand how the process works.

“Phone bank” is a term referring to any large group of campaign volunteers who cold-call potential voters in an attempt to ensure that they will vote for a particular candidate. Traditionally, such “get out the vote” drives are held inside campaign offices, using rows of phones provided by the campaign itself. But this phone-banking event was very modernistic: It was held in a public park, and volunteers were asked to use their own cell phones to make the calls — an additional benefit to the campaign, since the volunteers thereby absorbed the long-distance phone charges.

This phone bank was open to all comers, advertised as a public event, so I showed up, cell phone in hand, to see what I could see.

At the main campaign table in the park, one of the organizers signed me up and explained the system: he handed me a couple sheets containing a list of registered voters, their phone numbers, and various codes by which to identify them. As explained below in more detail, next to each name was a series of check-boxes which I was to fill out, indicating how the call went. [I blurred out all last names and phone numbers in the photo, to protect people’s privacy.]

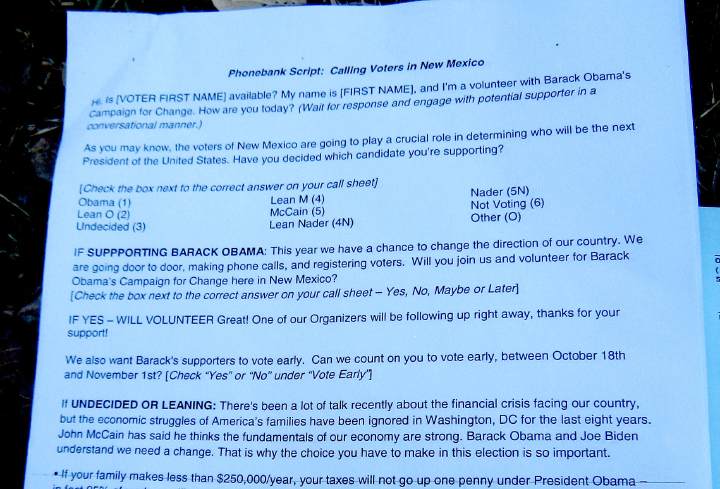

Next the organizer handed me a “Phonebank script” which he explained I could refer to during the call. He assured me that I didn’t need to refer to the script — it was only there as a handy reminder of what should be said, and as a cue-card in case I got stage fright and froze up during the conversation.

Interestingly, the script only had instructions for what to do if the person on the line was either an Obama supporter or was undecided. I asked what we were supposed to do if the person was a McCain supporter, and he told me: If that happens, just end the call as quickly as possible and move on to the next one.

Before I actually started calling, I asked one of the many assistants who were circulating through the park a few questions about the list I had been handed, and how I was supposed to fill out the check-boxes. She explained: The first column is for those calls in which you don’t reach anyone — fill in the appropriate box indicating what happened, i.e. No answer/message machine; refused to speak to me or slammed down the phone; respondent only spoke Spanish (I was calling New Mexico, since it was a “swing state”); or the number had been disconnected. But if they answered and were willing to talk, I moved to the next column: First I should ask who they’re voting for, and check the appropriate box on the form. If they’re voting for McCain or Nader, check the box but then end the call immediately and move on to the next call. If they are Obama voters, ask them if they’ve voted early; if they haven’t, encourage them to do so; and ask if they want to become volunteers. Then go on and ask about their preference in the New Mexico senate race.

I asked what the last column meant; she told me that “EV Location” was the nearest “early voting location” where the respondent could vote before election day. I asked how we knew what the nearest location was, since we didn’t have their addresses; she said that the address of each voter was in the database, it just wasn’t printed on the handout.

She also said that I shouldn’t expect to have too many actual conversations, because most of the time I’ll only be filling out column 1: Not Home/Refused/Spanish/Wrong #. She added, “Sometimes, you’ll call all nine numbers on a sheet and not get a single answer.”

So I got to work and started making some calls on my cell phone. Turns out the volunteer was right: Almost none of the calls were successful. I had been given two sheets, each listing nine voters, and out of the 18 calls I made:

3 had no answer

4 were message machines

7 answered but didn’t want to talk or immediately hung up

2 were disconnected numbers

1 was an Obama voter (who would vote on election day but who didn’t want to volunteer)

1 was a McCain voter

Which really got me to thinking, especially in relation to various arguments I made in my recent essay The Left’s Big Blunder. It was obvious to me that the Obama campaign was using these phone banks to generate statistics for voter preferences: they compile the answers that we phone-bankers record all over the country, and come up with percentages for their “internal polls” about how many people are planning to vote for Obama, McCain, etc. In my micro-sample, it was a 50-50 split. But what concerns me are those 14 people (out of 16 calls, excluding the wrong numbers) who either didn’t answer, or who hung up after answering. Why did those seven people hang up on me? Why did they not want to be polled? I’m sure the answers are varied and unique to each person, but could it be that one or two or more of them didn’t want to have a political discussion with an Obama campaign volunteer? And the four other people who let the answering machine get the call and three who didn’t answer at all — did any of them have caller ID and not answer because a stranger was calling? Why?

I feel, as I surmised in my essay, that any polling samples generated this way are potentially way off, and exclude most voters who simply refuse to be polled. The real question is: How do those people intend to vote? Because the “unpollable registered voters” demographic is likely to be the largest demographic of all. And we have no idea how they intend to vote, nor why they refuse to be polled, and if there is some correlation between refusing to talk to an Obama campaign volunteer and refusing to vote for Obama. Could the same principle hold true for calls made by professional polling organizations?

But most disturbingly of all: The Obama campaign knows the name, phone number and address (as the assistant told me) of each person called; and we volunteers do in fact mark down the voting preferences of each individual. So, through phone banks like these, should Obama in fact become president (and even if he doesn’t), he and his team will have a pretty extensive list of everyone who voted against him.

Hmmmm.

Food for thought.

A vendor was selling these shirts at the event; I really wanted to get a clear photo of one, but instead all I got was this blurry image. Oh well! But it confirms the thesis in my earlier essay (linked above) that Obama’s supporters are doing everything they can to declare his victory a foregone conclusion.

I decided that calling two pages’ worth was enough for the day. I turned in my sheets, picked up an Obama button, exchanged pleasantries with the organizers, and went on my way.

51 Responses to “Volunteering at an Obama Phone Bank”